The ‘Kirillovsky Palace’ and Collections

Nicholas B.A. Nicholson

In February of 1907, after two years of exile abroad, Grand Duke Kirill received a telegram from his mother Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna which read simply “Ta femme est Grande Duchesse.”[1] As Kirill later wrote in his memoirs, “these few words meant that all had been restored to me and that I could now return. Thereafter, the Emperor and Empress showed the greatest kindness and sympathy to both of us.”[2]

The return of Grand Duke Kirill was, in fact, a brief period of the restoration of a fragile harmony within the Imperial family. The outward break between the Emperor Nicholas II and his wife with the family of his Uncle Grand Duke Vladimir was further bridged by the Grand Duchess’ Maria Pavlovna’s conversion to Orthodoxy in 1908, and the Grand Duke’s deathbed in 1909. Kirill wrote that his brother Grand Duke Boris “had been working hard for my complete rehabilitation in Russia,”[3] and with the funeral of Grand Duke Vladimir, he was forgiven, and finally able to return to his naval career, his position as third in line for the throne, and to the St. Petersburg society which his mother ruled.

Kirill had lived as a young man in apartments in his parents’ house, the Italian Renaissance style palazzo at no. 26, Palace Embankment. The Vladimir Palace was an opulent historicist showplace, built by his father in the heady autocratic days of Alexander II, and it was to be among the last of the city palaces constructed for a Grand Duke. Later, as a bachelor, Kirill had shared offices with his brother Grand Duke Boris at No. 40, Moika Embankment,[4] and in 1898-1899, the young Grand Duke was given an apartment at on the first floor of the Hoffmeister building at Millionaya Street, 27. The apartment was decorated by the British firm of Maples, who were paid 10,000 British pounds, a sum equivalent to 99,802 roubles.[4a] Now, however, Kirill required a townhouse of sufficient dignity for his young family, and with the permission of Nicholas II settled his family temporarily in one of the early 19th century Cavalier’s House at Tsarskoe Selo on Galernaya Street, near his parents’ country place, the Vladimir Villa.

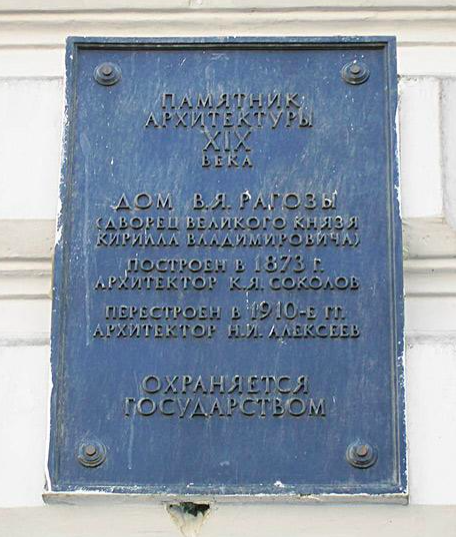

In 1910, St. Petersburg was awash with imperial properties, and so Grand Duke Kirill and his wife were offered a well-located house at 13 Glinka Street. The house was a few blocks from the Naval Church in the Nicholas Gardens, very close to Grand Duke Kirill’s naval offices, and close to the Mariinsky and other theaters. Not a palace, per se, but a very grand town house, the building had originally been designed in 1873 by the architect K.Ya. Sokolov for the nobleman V.Ya. Ragozy[5]. Constructed in the renaissance revival style, the building had lesser public and service rooms at street level, a comfortable open staircase which led to a “piano nobile” with public rooms of excellent proportions facing either Glinka street or the interior courtyard, and an attached rear building with a separate courtyard entrance which led both to the private quarters and the service wing. Sokolov had enriched the building with many fine and magnificent ceilings in carved wood and molded plaster based on designs from the Pitti Palace and other Florentine landmarks.

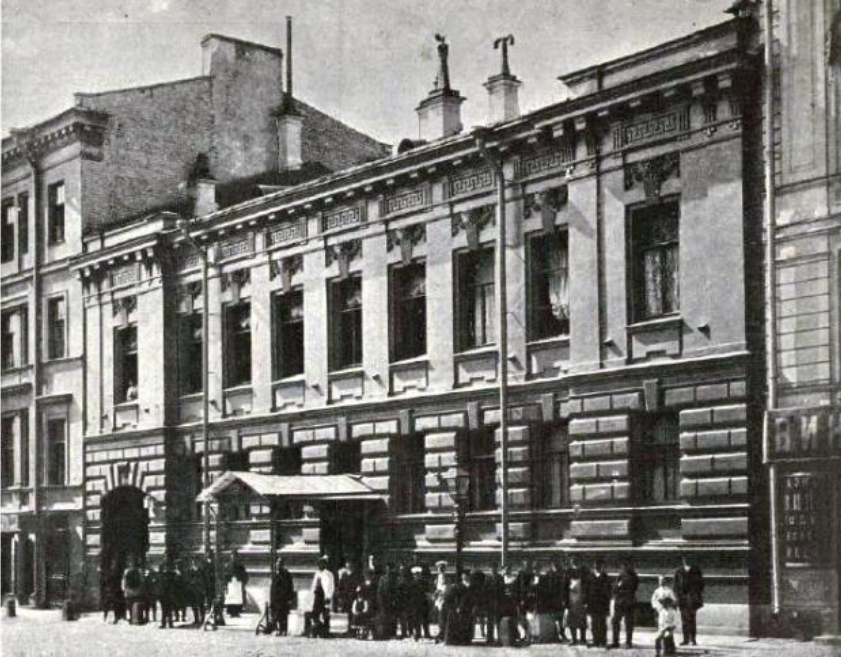

The house during its perioD as the Empress Maria Alexandrovna Home for the Protection of the Blind, ca. 1905.

The house had been acquired from the Ragozy family by the Imperial Chancellery for use for use as The Empress Maria Alexandrovna Home for the Protection of the Blind (Дом попечительства имп. Марии Александровны о слепых) and in 1904, the house had been extensively redesigned on the exterior and interior in the newly fashionable neoclassical style by the architects V.P. Apyshkov and G.G. Krivosheyn[6], who kept many of Sokolov’s original interior efforts. By 1910, the Home for the Protection of the Blind had outlived its institutional purpose, and the building had become available.

Grand Duchess Victoria, herself an artist, likely had definite visions for the new residence, and on her arrival in St. Petersburg, Victoria Melita needed to meet several agendas, familial, social, and artistic. Firstly, she had arrived in Russia with her two small daughters, the princesses of the blood Maria and Kira, and needed a pleasant home in which to raise her family. Secondly she needed a place suitable for the type of entertaining expected of the consort of the third in line to the throne. And finally, while her marriage to Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse had been a misery, Victoria Feodorovna had been deeply affected by the work of her ex-husband in his founding of the Darmstadt Artist’s colony in 1899. His motto was: "Mein Hessenland blühe und in ihm die Kunst,”[7] and Ernst Ludwig had established the chief artisans of the Art Nouveau in Darmstadt: Peter Behrens, Paul Bürck, Rudolf Bosselt, Hans Christiansen, Ludwig Habich, Patriz Huber and Joseph Maria Olbrich. They advocated original methods and manners of living, and Victoria Melita had been an ardent advocate of their work, and she likely hoped to make an original artistic statement in St. Petersburg.

Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kirill hired the architect N.I. Alexeev for the modifications. Alexeev had been the architect for Grand Duke Kirill Grand Duke Boris’ offices on the Moika, and he was well versed in the latest St. Petersburg classicism. Alexeev was responsible for many of the most handsome neoclassical revival and ‘Moderne” apartment buildings in St. Petersburg[8]. The house of the Grand Duke Kirill was under construction at the same time as the new apartments being constructed for Princess Irina and her husband Prince Yousoupoff, and there may have been some gentle competition.

The house today, after the Alexeev modificatons of 1910-1911.

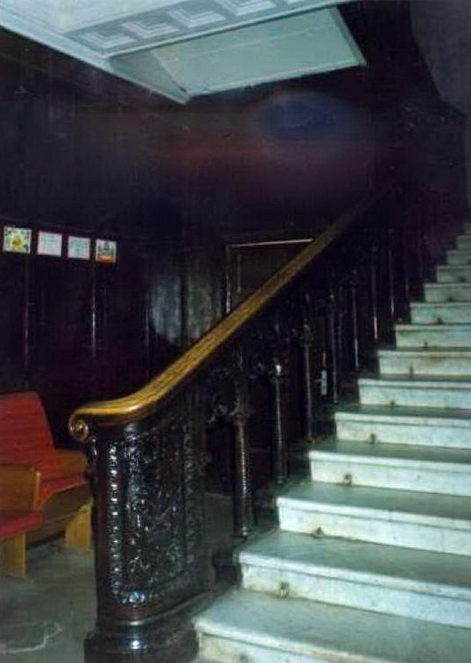

A view of the Entrance hall’s second floor with the door to the main Salon. Photo: Sergekot

Alexeev kept many of the exuberant renaissance revival details which remained from the original Sokolov décor, and some of the later neoclassical elements of the Apyshkov/Krivosheyn reconstruction but reconfigured the stair hall to improve the size of the rooms and the flow throughout the public spaces. The walls were painted or in polished white scagliola, and the elaborately treated ceilings and floors served to anchor the collections of the Grand Duke, who had acquired a large and interesting collection of Chinese imperial porcelain and Asian works of art during his travels in the far east. Kirill had also collected naval paintings and had acquired valuable pieces from the Russian Imperial porcelain factory by his mother. Victoria Feodorovna found herself the recipient of many of the most important Russian items which had been given to her mother, Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna by her parents on her wedding to the Duke of Edinburgh and brought her collection of paintings from Darmstadt and Coburg together with a fine collection of Darmstadt ceramics.

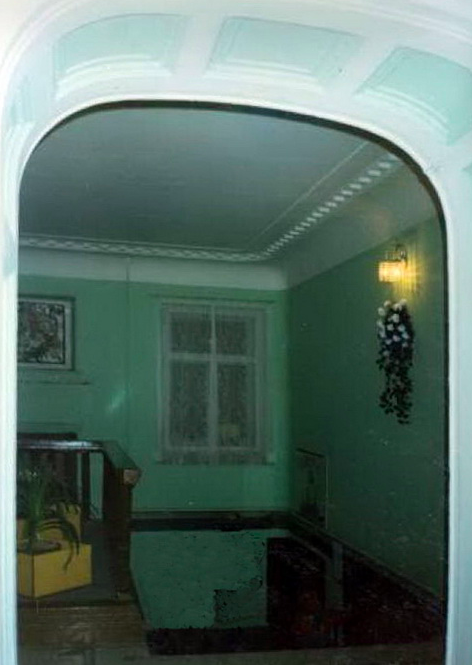

The art nouveau cabinetry still in situ at 13 Glinka Street. Photo: Sergekot

Alexeev created an art nouveau library-cabinet for Victoria Feodorovna with sinuous art nouveau mahogany paneling and casework in which to display her ceramics and family effects. We know also from contemporary photographs that there was a small sitting room with silk lampas-covered walls and white-lacquered furniture. The overall effect of the new residence was bright and comfortable, and it is widely cited that the “Kirillovsky Palace” (as it was now generally known in Petersburg) was a “cheerful” house[9], with children and dogs given completely free reign in all spaces. Like her first cousin the Empress, Victoria was a hands-on mother, and attended all her children’s lessons, speaking to them in English and in French as well as in Russian.

The family’s life in the house was not a long one. War was declared in the summer of 1914, and while Grand Duke Kirill was busy with his duties in the Naval Guard, Grand Duchess Victoria chaired numerous wartime efforts, most particularly those which touched the expatriate British community in Russia. The resident “English princess,” in St. Petersburg Victoria was on the board of the Anglo-Russian Hospital located in Grand Duke Dmitri’s Palace on the Fontanka Embankment.

By early 1917, Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kirill were the only Romanovs left in Petrograd. The Empress and her children were at the Alexander Palace and the Emperor was at the front, Grand Duke Nicholas and his family were in the Caucasus to which he had been exiled. The Dowager Empress and her daughter Grand Duchess Olga were at Kiev, the Konstantinovichi were at the front or at Strelna or Pavlovsk,the Mikhailovichi clan were all in the military, and the Pavlovichi were at Tsarskoye Selo. As the revolution hit, and the situation became worse, it became clear that Grand Duke Kirill and his wife would have to leave[10].

Grand Duke Kirill and his cousin Grand Duke George Mikhaiovich petitioned the Provisional Governement to allow them to leave Petrograd for a safer place in Finland. In June of 1917, Grand Duke George was given permission go to the duchy of Finland and rented a villa at Retierve, a small village. Grand Duke Kirill was subsequently granted permission to leave in the same month, and later, at the urging of the six-month pregnant Grand Duchess Victoria, left with his daughters by train for Helsingfors (Helsinki), and later for a rented villa at Poorvo. Grand Duchess Victoria’s motivations for sending her husband and children first were clear. She had been born a princess of Great Britain and Ireland and had been promised protection by the British Ambassador George Buchanan. As her husband was next in line to the throne, she regarded his safety and that of her children as of paramount importance; she may have thought that even the revolutionaries would have the decency to leave a pregnant woman alone.

Grand Duchess Victoria went through the house to secure as many valuables as possible. She managed to get away with most of her important jewelry, including the “Edinburgh suite” of sapphires made for her mother’s wedding to the Duke of Edinburgh by Bolin[11]. She gathered as much jewelry as she could, hiding it in her maid’s luggage, and immediately arranged for a container of furniture and art objects to be sent on to Finland. Among those things that we know of were several important pieces of Imperial Porcelain, as well as a silver-mounted Karelian birch tea table by Fabergé which had been a gift from her mother-in-law[12]. By early July, Grand Duchess Victoria was in Finland with her family, and in August, their son Wladimir was born.[13]

The house, sealed by the Grand Duchess, was left in the care of the servants. By early June, various Bolshevik subcommittees were already angling for the objects of value which had been left behind in the former imperial palaces. On the 17th, the following order was issued:

“Artistic and Historical Commission at the Winter Palace”

June 17, 1918

No. 154. Certificate

The commission certifies that its employee, Fedor Fedorovich Noftgaft, is entrusted with the task of transporting objects of artistic and historical significance from the palace of the former [бывший] Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich (13 Glinka St.) to the Winter Palace.

Chairman of the Commission V. Vereshchagin.

Secretary A. Trukhanov[14]

Noftgaft, born in St. Petersburg in 1886, was a noted collector who had commissioned a portrait of his wife from Kustodiev in 1913. He had been brought in by the Petrograd Soviet to help catalogue the Romanov collections in the suburban palaces, likely due to his close connections to many of the artists of the day, who served on the various arts committees of the Hermitage and former Museum of Alexander III. A paintings connoisseur, he was dispatched to the Kirillovsky Palace to take stock. In only one day, it appears, Noftgraft returned to the Winter Palace with the most valuable objects, culled from an inventory made in the presence of the Grand Duke’s attorney, Vsevolod Nikolaevich Boev .[15] The inventory includes vague descriptions of pieces which now untraceable: No. 4, a “porcelain elephant” and No. 31, a “gilded vitrine with 106 oriental objects in stone, faïence, and wood” stand out as possible lost important objects.[16]

ACT

On June 17th, the Art and Historical Commission at the Winter Palace accepted those objects brought to this Palace from house No. 13, Glinka Street in Petrograd, by an employee of the commission F.F. Notgaft, those objects of artistic and historical value belonging to the former [бывший] Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich Romanov listed in the compiled list attached herewith, with the exception of No. 17 (a yellow Chinese ceramic vase) and No. 18 (an old panel painting [on Muntian wood?]).

Chairman of the Commission V. Vereshchagin.

Secretary A. Trukhanov[17]

It was not until the 19th of July, 1918 that it was announced that all Romanov properties were nationalized, and all their goods were the property of the state. The Kirillovsky Palace had already been denuded of the Romanovs’ treasures, just one of the many former imperial residences which were deconstructed and whose valuable objects moved to other locations and collections.

In his 2018 study ‘Revolution and Collections” Ivanov notes that the most important works of Chinese and Asian art from the collection of Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kirill were sent to the Ethnographic Museum in Leningrad. The paintings of any value were divided between the Hermitage and the newly renamed State Russian Museum. Very few of these objects maintained their Imperial provenance as they traveled, but the core of Grand Duke Kirill’s collection, his naval paintings, were transferred by the Museum Commission to the Central Naval Museum, and some are identified as having survived in that collection to the present day, including works by A. Begirov, L. Blinov, K. Kranozhitsy, and K. Krzhitsky.

13 Glinka Street was requisitioned and served various functions as its moderne interiors gradually degraded through use and antipathy to their origin. The Palace was badly damaged during the Siege of Leningrad, though much of what remains would be familiar to Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria. The Salon where Grand Duchess Victoria served tea from her Fabergé service retains its ceiling and architecture, and her art nouveau cabinet remains virtually intact.

After the war, the palace was again reconstructed in the late 1940’s, and became known as the “October” Kindergarten where many of Leningrad’s children first went to school. In that capacity, the building may have once again, to a certain extent, become the “cheerful” place noted by the friends of the man and woman who would become known as the “Emperor and Empress-in-exile.”

NOTES

[1] Grand Duke Kirill, My Life in Russia’s Service, London: 1939, p. 185

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Gostinitsa Demut” from Citywalls Arkhitekturnii sait Sankt-Petersburg, https://www.citywalls.ru/house3185.html, (retrieved May 6, 2020).

[4a] Korneva, Galina, & Tatiana Cheboksareva Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna, Linie Rossii/Eurohistory, Richmond Heights, CA: 2016, p. 57.

[5] ‘Дворец Кирилла Владимировицча', Путешествуя Историей, https://sergekot.com/dvorets-kirilla-vladimirovicha/ (retrieved May 6, 2020.)

[6] ‘Дом попечительства имп. Марии Александровны о слепых’, Citywalls Arkhitekturnii sait Sankt-Petersburg, https://www.citywalls.ru/house309.html, (retrieved May 6, 2020).

[7] “My Hesse should flourish, and in it the arts.” (Trans – NN)

[8] These include the magnificent Lermontov Pr. 8A, and the Lazarev Apartments at Kamennoostrovskii Prospect, 27.

[9] Reshetnikov, Evgeniy, ‘Дворец великого князя Кирилла Владимировича’, О Петербурге с любовью, https://spbinteres.ru/dvorec-bobrinskix-spb.html, (retrieved May 6, 2020).

[10] The complications of the February days are beyond the scope of this article which is dedicated only to the house and its collections.

[11] Grand Duchess Victoria sold the necklace and the two-part stomacher with a large triangular diamond to Cartier, Paris, in the 1920’s. (cf. Van der Kiste, John, Princess Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia, London, 1991.)

[12] Fabergé scholar Valentin Skurlov notes that the Silver tea service had been an 1899 Silver wedding anniversary gift to Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna and her husband Grand Duke Vladimir. The service was later presented to Kirill and Victoria in 1910. The Grand Duchess subsequently gave the table to the new Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco where it remains today, (Inv. No. 1945.355-357.). The Grand Duchess sent the piece from Coburg to San Francisco with the following letter:

Dear Mrs. Spreckels,

Having heard of your wonderful new museum, and of all you are doing to help my sister the Queen of Roumania [Mrs. Spreckels raised money for medical supplies for Romania], I wish to present you with a golden [silver-gilt] tea service made by our famous Russian artist 'Fabergè. It is one of our few treasures saved and I am glad if it can find a place in the glorious monument you are building to the memory of your California soldiers. It has always been a tradition in the Russian Imperial family to help whenever they could, however they could, and wherever they could, and as at this moment we cannot build anything in remembrance of our own millions of fallen brave, who fought and fell for the same cause, I am happy to offer a token of respect and regard to your 3,600 California sons whom you are immortalizing.

Yours very sincerely,

Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Kirill of Russia (cf. https://www.famsf.org/blog/framework-imperial-tea-service-peter-carl-faberg

[13] Grand Duke Kirill, p. 215-216.

[14] Ivanov, Революции и Коллекции: Петроградское (Ленинградское) Отделение Государственного Музейного Фонда и Музей антропологии и этнографии. Санкт-Петербург: 2018, pp. 118, citing TSGALI. F. 36. Op. 1. D. 1a. L. 53.

[15] Ivanov, Материалы по латиноамериканистике в МАЭ в начале ХХ в., Санкт-Петербург: 2018, p. 24-25

[16] Ibid, p.26, citing TSGALI F. 36. Op. 1 D. 1a L 8 ob.

[17] Ivanov, Революции и Коллекции, p. 119, citing TSGALI. F. 36. Op. 1. D. 1a. L. 64