Since its initial release several years ago, I have found other pieces of information which expand upon this article which were unavailable at the original time of publication in Royal Russia Annual No. 6 (Summer 2014). I remain grateful to Paul Gilbert for his early interest in this subject. . While the piece is similar to the original, there are new sources of information, and it is hoped that by placing the article on this website, it will find a new and broader audience.

“How Lovely A Country This Is”

Part I

The story of the voyage of Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna to the United States, 1924.

December 13, 2013 New York City: Head of the House of Romanoff attends Patronal Feast Day Celebrations of Synodal Cathedral of the Sign. Photo: Eastern American Diocese, R.O.C.O.R.

From the 9th to the 14th of December 2013, H.I.H. the Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna of Russia made a private visit to the United States at the invitation of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad to commemorate the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the End of the Time of Troubles and the Foundation of the Romanov Dynasty.[1] The Grand Duchess was received with honors as Head of the Imperial House by Metropolitan Hilarion (Kapral), First Hierarch of the Church Abroad, and attended a divine liturgy on the feast day of the Wonderworking Kursk-Root Icon of the Mother of God at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign in New York City. The Divine Liturgy was concelebrated by the clergy of the Orthodox Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate.[2] The New York visit of HIH Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna was of historical significance, not only as an indication of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad’s continued recognition of the legitimist claim to the throne (it had also recognized HIH’s father, Grand Duke Vladimir, and her Grandfather, Grand Duke Kirill, as the Heads of the Imperial House), but also because it continued a long line of official, semi-official, and private visits made by members of the Imperial House to New York in the decades after the Revolution of 1917.[3]

Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kyrill of Russia, ca. 1910

Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna’s visit was almost 89 years to the day that her grandmother, the Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna, arrived in New York to begin a 10 day “goodwill” tour to thank American supporters of Russia for their continued aid to her Russian homeland and to Russian refugees during the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Russian Civil War.[4] The Grand Duchess’ 1924 trip was marked with great interest and social successes, but the trip also occasioned the appearance of a pattern of arguments against the legitimist claim to the throne that are still repeated today, particularly in the West, where access to Russian primary sources has always been slender. Western historians, in fact, often quote newspaper reports of the period without much further examination or corroboration of their accounts, which has served only to validate, through repetition, these early and biased arguments.

Victoria Feodorovna’s husband, Grand Duke Kirill (de jure Emperor Kirill I), had paid New York a semi-official visit in 1899, while returning from active duty in the Russian Imperial Navy in the Sea of China[5]. Interviewed by the New York Times shortly before his departure for Russia, the Grand Duke commented regretfully that he had not been able to enjoy the United States in summer, but that he had very much enjoyed his trip. In the interview, the Grand Duke showed himself to be an elegant man and a diplomat, easily discussing Russian and American involvement in Asia in the most encouraging and friendly terms, while avoiding the sensitive subjects. Reports presented him as both handsome[6] and engaging:

“He made his appearance in a frock coat that was buttoned up and wore a broad moiré silk necktie in which was pinned a small gold bear's head with ruby eyes. He wore several rings on his fingers and a gold chain bracelet on his left wrist. When asked about his impressions of America he said that his sojourn here had been so brief, and most of what be saw was from a parlor car window. ‘There was snow all around,’ he added, ‘and I did not have the pleasure of seeing the plains and valleys of this great country in their glorious mid-summer dress. And when we got to Niagara Falls it was already dark, and I was unable to make out that magnificent waterfall, and had to content myself with listening to the roar of its waters. We stayed several hours in Chicago, and there I took a look at some of the tall buildings that you call sky-scrapers.”[7]

While in New York, the Grand Duke was entertained privately, but made a few public appearances, the most important being a reception hosted by the Russian Ambassador, Count Cassini, Consul-General Teploff, and the rest of the Russian Legation at the consulate. He also attended a moleben (service of thanksgiving) at the new Russian Church of St. Nicholas at 290 Second Avenue between 18th and 19th Streets.[8] The Grand Duke and the Ambassador were received by the entirety of the New York City Orthodox clergy, amongst them Bishop Nicholas of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska,[9]Archimandrite Raphael of the Syrian Orthodox Chapel in Washington Street,[10] and Father Alexander Hotovitzky.[11] Prayers were offered on behalf of the entire Imperial Family, and the Grand Duke then met with members of the New York Russian community. After the service, he was escorted to the “Russian Club,”[12]where, after the singing of “God Save the Tsar,” some welcoming comments by H.E. Consul-General Teploff, and a performance of “Sailing Down the River, Mother Volga[13]” by the club’s female members, he was unanimously elected Honorary President of the organization. Grand Duke Kirill thanked them with a toast to their continued prosperity, and then returned to the Waldorf-Astoria. The Grand Duke attended the theater that night, and left New York the following day with Bishop Nicholas of Alaska, who was returning to Russia; they sailed together for Genoa on the Fuerst Bismarck.[14]

H.I.H. Grand Duke Kyrill of Russia, ca. 1905

The Grand Duke and his family had long standing and friendly relationships with prominent members of American society for quite some time. Grand Duke Kirill’s mother, the Grand Duchess Vladimir (Maria Pavlovna the Elder) had been known before the revolution for her wide circle of international friends and acquaintances that included many Americans living in Europe. Her circle included the Duchess of Marlborough (née Consuelo Vanderbilt)[15];Princess Michèl Cantacuzène, Countess Spéransky (née Julia Dent Grant)[16]; and even the popular author Elinor Glyn[17], who visited the Grand Duchesses Maria Pavlovna and Victoria Feodorovna during the 1909-1910 Winter Season in Saint Petersburg, and whose impressions of pre-revolutionary Russia were gathered in her best-selling novel, His Hour.

Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria made further American friends during their residence in Paris immediately after their marriage, including the American heiress Anna Gould[18] and other members of the American expatriate community in Paris. The Grand Duke’s brother, Grand Duke Boris, had formed his own contacts, making a social sensation while visiting Chicago, New York, and Newport in 1902, renewing relationships made by his brother and calling on friends of his mother’s. The members of the “Vladimirovichi” branch of the Imperial Family had solid relationships with American society in Russia, in France, and in the United States that proved to last long after the Revolution.

The Imperial House was very large, but not particularly close to one another. Members of the Dynasty tended to stay within their “branches,” and only gathering publicly for state occasions. H. G. Graf, in his invaluable memoirs In The Service of the Imperial House of Russia 1917-1945, put it best:

The Imperial family was not closely knit during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II…there were a number of grand ducal courts in Imperial Russia, and the retinue and friends of each of them could have a significant influence upon prevailing attitudes. There were the large Court of Emperor Nicholas, the Court of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, the Courts of the Vladimirovich, the Pavlovich, the Constantinovich, the Nikolaevich and the Mikhailovich. These branches of the Imperial Family lived in harmony within their own circles for the most part, pursuing their own affairs. The entire Imperial Family would gather at the Large Court on official occasions, such as celebrations or holidays, but only occasionally might two branches, or individual members of different branches, have other than formal social contact.[19]

During the reign of Nicholas II, this isolation increased as the number of large, public events at which the family had the opportunity to gather dwindled after 1903. The tercentenary celebrations of 1913 failed to unite the large family in any meaningful way; in point of fact, the large celebrations seemed to impress the family most with how divided they were from one another and how conflicted they were over the threat of war and the worsening domestic political situations in Russia[20].

H.M. The “Emperor-In-exile” Kyrill I Vladimirovich

The turmoil of revolution and the subsequent Civil War and unrest in Russia and in Europe further divided the members of the Imperial Family by location, by political opinion, and by personal loyalties. They were not bound together by the horrors they had experienced and, as Graf regretfully summarized, the tragic deaths of 20 of the members of the Imperial Family did not galvanize the family into a single unit, but heightened their grief, their political differences, and their personal disputes.[21] These divisions began to play out in public when Grand Duke Kirill declared himself “Curator” of the Russian Throne in 1923[22], and then again on August 31, 1924, when Grand Duke Kirill issued his Manifesto on his assumption of the throne.[23]

All the senior members of the dynasty were in agreement that Kirill was the next in line to the throne under the prerevolutionary Fundamental Laws of the Empire, but Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaevich, his brother Peter Nicholaevich, and his nephew Roman Petrovich refused to acknowledge either Kirill’s claim or that the Fundamental laws were still valid after the revolution. Many felt that Nicholas Nicholaevich would make a better Tsar, and his immediate family shared that opinion. While Grand Duke Nicholas was the oldest living Romanov male, the Nicholaevichi were not dynastically senior and were actually amongst the furthest from the throne under Russian Imperial Law, which was based on senior male descent from the most recent Emperor. Grand Duke Nicholas, while never formally announcing a rival claim to the throne, nevertheless tolerated supporters of his cause and political agitators in the use of his name in deriding Kirill’s claim. The Nicholaevichi were the only members of the Imperial Family that refused to sign the oath of allegiance to the new Emperor.[24]

This rift within the Imperial Family was used to great advantage by the various political groups that kept the Russian communities in Paris, London, and Berlin divided along political lines. There were liberal democratic Russian groups, republican Russian groups, socialists and nationalists, as well as monarchists; and while it was clear that the monarchist group was the largest, it was now split between Legitimist-Monarchists, who sided with Grand Duke Kirill, and multiple opposing groups, some of whom advocated Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaevich[25]as a candidate, but yet still others that looked for other dynastic members of the Imperial Family to serve as new candidates to serve at the head of their cause. Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich was later approached by several splinter monarchist groups as he was the next in line in the legitimate succession after the young Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich and Kirill’s brothers Boris and Andrei. Grand Duke Dimitri refused, noting that the oath of loyalty he had taken to the Emperor to uphold the Fundamental Laws[26]prevented any such thought of the throne. For Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, the Fundamental Laws were both sacred and inviolable.

Immediately after his announcement, Grand Duke Kirill made a trip to meet with members of the Russian community in Paris, the second largest in exile. While he felt that the trip went very well, it was clear to him that there was a vocal and sizable group that favored Grand Duke Nicholas’ claim to the throne. Aware of this, Grand Duke Kirill returned to Coburg, well enough satisfied by the result of the trip, but also well aware of the delicate political situation created by his accession to the right to the throne under Imperial Law by those who, without legal foundation, felt that those laws were no longer valid.

Grand Duchess cyril with her son, Grand Duke Vladimir, ca. 1919.

The Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna, now de jure Empress in the eyes of legitimists, was concerned for her husband’s position, as well as her son’s and her own, but nonetheless fulfilled her duties as consort of the Head of the Imperial House. Since her acceptance into the family, and her recognition as Grand Duchess with full dynastic rights by Nicholas II,[27] Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna had proved a popular and dutiful member of the Imperial House,[28] working in her mother-in-law’s hospitals, and even inspecting British warships with the daughters of Nicholas II,[29]with whom she visited regularly just before the outbreak of World War I.[30] After the Revolution, in Finland, in France, and at Coburg, the Grand Duchess never ceased to lend her name and her support to any legitimate organization that was working to alleviate the suffering of Russians or of Russian refugees abroad; and by the early 1920’s, a great deal of this work was being done in America by Americans.

Early in 1922, the Grand Duchess Victoria had heard from her sister, Queen Marie of Romania, that in addition to helping with Romanian Relief efforts, the Spreckles family of San Francisco had begun to fund and build the Museum of the Legion of Honor in California. Immensely moved by this action to honor the dead of World War I, the Grand Duchess immediately wrote Alma Spreckles in California:

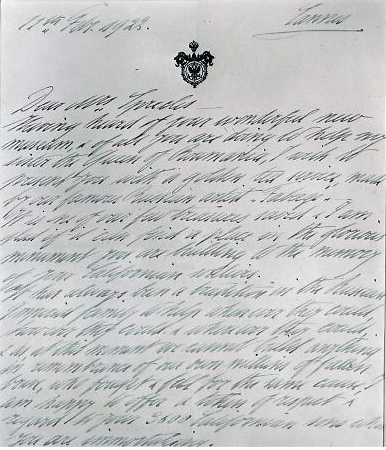

The Original letter from Victoria Melita, San Francisco

Having heard of your wonderful new museum, and of all you are doing to help my sister the Queen of Roumania, I wish to present you with a golden tea service made by our famous Russian artist Fabergé. It is one of our few treasures saved and I am glad if it can find a place in the glorious monument you are building to the memory of your California soldiers. It has always been a tradition in the Russian Imperial family to help whenever they could, however they could, and wherever they could, and as at this moment we cannot build anything in remembrance of our own millions of fallen brave, who fought and fell for the same cause, I am happy to offer a token of respect and regard to your 3,600 California sons whom you are immortalizing.[31]

From that first kind donation of her silver-gilt mounted Karelian birch tea service, the Grand Duchess seemed aware that help for Russia, for Russians, and perhaps for her own husband’s cause might come from the United States and its generous and enthusiastic people. Later that year, or possibly in early 1923, the Grand Duchess had been placed in touch with Mrs. Henry P. Loomis of New York, most likely through Princess Cantacuzène, Countess Spéransky, who was well-known to both women.[32]

Peter Carl Fabergè (Russian, 1846–1920). Julius Alexandrovitch Rappoport (workmaster). Tea Service with Tea Table, 1896–1908. Silvergilt, Karelian birch, ivory. Gift of Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Kyrill of Russia, through Alma de Bretteville Spreckels. 1945.355-357.

Mrs. Loomis was a quiet force in New York Society. A member of the Colony Club,[33]president of the New York Chapter of the Colonial Dames of America,[34]and a Chairwoman of the Metropolitan Opera’s elite “Monday Opera Supper Club,[35]” Mrs. Loomis had taken interest in the plight of Russian émigrés after hearing Princess Cantacuzène lecture in New York. Through the princess’ connections, Mrs. Loomis was able to secure the names of many members of the Russian Imperial Family to aid her in raising money for Russian refugees in the United States through the Russian Relief Fund.[36]

On November 26, 1923, Mrs. Loomis, together with Princess Cantacuzène, Countess Spéransky, Mrs. Richard Mortimer, Mrs. Henry H. Rodgers, and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt (friends from the “Monday Opera Supper Club”), she hosted the first of a series of “relief benefits” at Sherry’s.[37] The Honorary Committee included Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria, Grand Duchess Xenia[38], Grand Duke Michael and Countess Torby, and the Prince and Princess Andrew of Russia.[39]The November event was a success, because the following summer, a benefit ballet performance directed by Michel and Vera Fokine took place in early August, with the same ‘Imperial Honorary Committee’ in place, and with the Russian Relief Fund benefiting from the performances.[40]

One can only imagine Mrs. Loomis’ excitement when Grand Duke Kirill’s announcement of his claim to the throne appeared in the European papers later that month, and it was certainly in September that she began agitating for the Grand Duchess to visit the United States personally. By the time Grand Duke Kirill had returned from Paris to Coburg, thanks to the wildly persistent Mrs. Loomis, the Grand Duchess’ trip to the U.S. was on everyone’s mind. According to H. G. Graf:

Upon our return another important matter was facing us: The trip to the USA of Her Majesty by invitation from the American Ladies Charity Club. This Club was chaired by the widely known Mrs. Loomis. It is a socially prominent club of the descendants of the first two hundred families to immigrate to America from England[41]. At the time the Club was involved in raising funds for assistance to Russian emigrants. Under the influence of her Russian secretary, C. Djamgarov[42], the Chairwoman came up with the idea of inviting Her Majesty Victoria Feodorovna to the USA to promote greater success in fund-raising.

Mrs. Loomis anticipated that the visit of Victoria Feodorovna, especially after the much talked assumption of the Imperial title by her husband, would generate a great sensation. Her presence at receptions and dinner parties organized by the Club in her honor would likely attract many rich and eminent Americans, thus increasing the collections.[43]

It was clear to both Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria that this kind of visit, one in which the Grand Duchess would be received with honors by distinguished members of foreign society, would be an advantage in consolidating support for his claim. Whether the Imperial Couple hoped for official U.S. recognition for their claim is unrecorded, but rather than dwell on the difficulties, they were ultimately persuaded by Mrs. Loomis’ assurance of success:

The Chairwoman requested Her Majesty to come with a retinue of two ladies and a man. All travel was to be on one of the best liners and in the most luxurious hotels, the grand scale expense to be born by the Club.

Many considerations made Her Majesty waver in her decision to go. Although she was receiving the best possible endorsements of Mrs. Loomis, Her Majesty did not know the woman well and was concerned about her tact in dealing with Her Majesty. Her Majesty was also reluctant to go at the expense of the Club since this would place her in a position of dependence and oblige her to act in accordance with the desires and needs of the organizers of the trip which might not concur with her own. Finally, she was worried about the stress generated by a month of traveling.

Yet Her Majesty understood the importance of this trip for the worldwide promotion of her husband's cause. It could also provide useful contacts in the USA and, not least help in gathering funds for the poverty-stricken Russian emigration.

After much vacillation, much advice and much correspondence with Mrs. Loomis, Her Majesty agreed to go.[44]

According to H. G. Graf, Grand Duchess Victoria chose as her entourage the Princess V. K. Meshchersky, Mme. Makaroff, and Rear-Admiral N. A. Petrov-Chernishin.[45]

*

In Washington DC, on the afternoon of October 24, 1924, Mrs. Robert Lansing, former Chair of the American Committee on Russian Relief told over 100 women assembled at her home that Grand Duchess Victoria would sail for New York on November 29. The announcement made the New York Times the following day.[46]

Mrs. Loomis confirmed the news from New York that day, when she announced that the Grand Duchess had telegraphed that she would be sailing in the “Paris”, and confirmed that she would be staying in the “Royal Suite” of the Waldorf-Astoria—the same rooms that had been occupied by Grand Duke Kirill before his marriage in 1899. A member of the Opera Club Committee insisted that the Grand Duchess was not coming to lecture, as some had said, but was visiting “simply in recognition of the efforts of the club to aid her suffering compatriots in Europe.”[47] New York was clearly excited at the prospect of another imperial visit, and friends of Grand Duke Kirill and Grand Duchess Victoria began planning the type of private entertainments expected for such a trip.

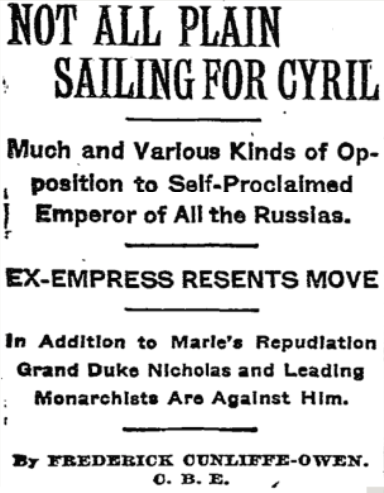

“Not All Plain Sailing”. New York Times, November 2, 1924

On November 2, however, a long article “Not All Plain Sailing For Cyril” by Frederick Cunliffe-Owen, C.B.E. appeared in the New York Times.[48] Cunliffe-Owen was well-known to New Yorkers for his biting wit and antagonism towards European Royal protocol and rank. Half-English and half-German, he had thumbed his nose at European nobiliary legal practice for years, and in 1912 had written scathingly of the concept of “morganatic” or “unequal” Royal marriages, insisting that he felt they were no longer necessary in a modern age.[49] Cunliffe-Owen was, despite his membership in the Order of the British Empire (as Commander), a deeply biased authority on the subject of legitimacy, and so it was a great misfortune for the Legitimist-Monarchist cause in general and for Grand Duchess Victoria in particular that it was Cunliffe-Owen who was the first to acquaint the American public with the details of what had happened in Paris regarding Grand Duke Kirill and his announcement of his accession to the throne. Thanks to its wide dissemination, the article cast a pall over the Grand Duchess’ trip, and its arguments have clouded American understanding of the Russian Succession question for generations.

Cunlifffe-Owen’s article began:

Since the former Grand Duke Cyril has not only issued a public manifesto proclaiming himself Emperor of all the Russias, and his seven-year-old son, Wladimir, as Czarevich, but also had it announced from Paris that he is very shortly sailing for New York with his aide-de-camp. General Sikoopsky, to confer with certain American capitalists, who are anxious to bring about through him the restoration of a monarchical government which would enable the United States to resume stable trade relations with Russia, it may be of timely interest to call attention to the peculiar position of this particular scion of the Imperial family of Romanoff, especially with regard to the other members of the dynasty.

Examination of Cyril's antecedents and present position is all the more timely since his consort, who was born as a princess of the reigning house of Great Britain and as a daughter of Queen Victoria's second and sailor son is to arrive here on November 29th as a sort of advance agent to pave the way for her husband’s coming by delivering a brief series of addresses under the patronage of Mrs. Henry C. Loomis’ Russian Relief Society.

Grand Duke Cyril is already acting and speaking as if he were assured of the monetary backing of financiers here.[50]

Cunliffe-Owen’s baseless assertions and his misrepresentation of the recent events in Paris clearly betray his personal opinions, and it is worth pointing out this journalist’s particular biases and personal contacts in more detail.

Mr. and Mrs. Ernesto Fabbri, ca. 1900. Mrs. Fabbri née Edith Vanderbilt Shephard

In 1917, Cunliffe-Owen sat on the New York working committee to welcome the Italian Royal Commission to New York[51]. The working committee included many American members of New York Society who would later welcome the Grand Duchess, but was also heavy with well-connected New Yorkers of Italian descent, including the famous Giulio Gatti-Casazza (Director of the Metropolitan Opera), publisher Agostino di Biasi (“Il Carroccio”) and millionaire Ernesto Fabbri[52], husband of Edith Shepherd Fabbri, a Vanderbilt heiress and personal friend of Queen Elena of Italy, the sister of the wife of Kirill Vladimirovich’s rival, Grand Duke Nicholas.[53]

Cunliffe-Owen states for the first time in print in the U.S. many of the arguments made against Kirill’s right to the throne, many of which are still used today by those who deny the Legitimist claim: that the Dowager Empress Marie would have nothing to do with Kirill and that she denied his claim to the throne; that Kirill was a supporter of the provisional government and had committed treason; that his marriage to his first cousin was prohibited by the church; that the Emperor had not recognized either his marriage or his heirs; and that he was not supported by General Wrangel, the majority of the Russian emigration in Paris, or the remaining members of the Imperial Family. Cunliffe-Owen even stated as fact that Grand Duke Kirill’s claim was fully supported by the Soviet Government as a communist move to fracture the pro-Nicholas monarchist movement. These arguments are largely outright fabrications, manipulated half-truths, or irrelevant to the question of Kirill’s succession, but the particular accusations that surface at this time began to influence the opinion of the American press, as well as the Russian émigré community in New York, many of whom had only had fractured or partial news of Kirill’s accession in Paris.

Rumors or no, the Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Monday Opera Supper Club, and the members of the Russian Relief Fund moved forward and moved fast with their plans for the Grand Duchess’ visit. The trip was expanded from a New York visit to one that included Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Interest in the trip did not wane despite anti-legitimist press from Europe. Even the fact that Mrs. Robert Lansing[54]had arrived in New York to discuss the plans for Grand Duchess Kirill’s trip merited placement in the Times.[55]

The late art nouveau grand staircase of the french line’s “Ville de paris” 1916.

All was quiet for the remainder of the month, until November 29, when the Grand Duchess set sail from Le Havre on the Ville de Paris. The Grand Duchess left with Mme. Makaroff as planned, but contrary to Graf’s memoirs, Princess Meshchersky did not come to America, and was replaced by Countess Orloff, “the widow of General Orloff who was assassinated.”[56] The Grand Duchess sent a message to American women via the ladies of the Opera Club: “Tell them of my joy at meeting them, and how happy I will be to thank them for all they have done for us.”[57]

The crossing, however, was a misery. Graf writes:

Unfortunately the crossing was spoiled by a violent storm, which continued for the entire voyage, causing the ship to roll and pitch badly. The scheduled entertainments chosen especially for Her Majesty had to be curtailed and at times even canceled. Many passengers were sea-sick. Both ladies of Her Majesty’s retinue suffered badly. Her Majesty, although not sick was not feeling too well and was fatigued by the rolling and pitching. Despite it all she did not miss a luncheon or dinner, always accompanied by Admiral Petrov-Chernishin. She was seated at the Captain's table in the place of honor. The attention of all those present was, naturally, focused upon Her, making it all the more difficult to appear unaffected by the motion of the ship.[58]

It is hard to imagine a more unpleasant beginning to such a journey.

As the boat drew closer to the American shores, the seas calmed, and the passengers had time to adjust and recover enough to participate in the final evening on board, on which there was a gala dinner, concert, and ball in the Grand Duchess’ honor as the Paris floated in the Atlantic just outside the Great Bay of New York. The Grand Duchess was seated at the Captain’s table with the former Governor of Massachusetts and his wife, Governor and Mrs. Fulham, and together they watched a Russian concert by violinist Samuel Dushkin, and pianist Helen Stromilo, performances by Russian dancers, and finally, Madame Makaroff, the Grand Duchess’ lady-in-waiting, spontaneously rose and recited poetry to great effect. The concert was followed by a dance lasting until four o’clock in the morning. The orchestra played everything from Viennese waltzes and gypsy music to the highly popular (and terribly modern) ‘Fox Trot.’[59]

The next day, the Grand Duchess and her small retinue sailed into New York harbor, and she was treated to the sight of the Statue of Liberty raising her torch towards the sea, and the new Woolworth and Singer buildings of the New York skyline rising from the tip of Manhattan between the Hudson River and the Long Island Sound. A convoy of little red tugboats appeared, spewing jets of water into the air to salute her arrival and to lead the ship to shore, where Mrs. Loomis had warned her in a letter, the coarse and persistent New York Press would be waiting for her.

View of New York Harbor, 1920’s, Underwood Archives.

Graf noted:

Mrs. Loomis forewarned Her Majesty that, as soon as the liner docked at the pier in New York, she would be assailed by an army of reporters asking questions, many of which would be impudent and capricious. The best way to react, she was advised, is not to become offended. One should try to be casual, witty and smiling. One should keep in mind that in the USA the press plays an important role in establishing the mood of the public's reception of a person or reaction to an event. Antagonizing the press could destroy the whole purpose of Her Majesty's visit to the United States.[60]

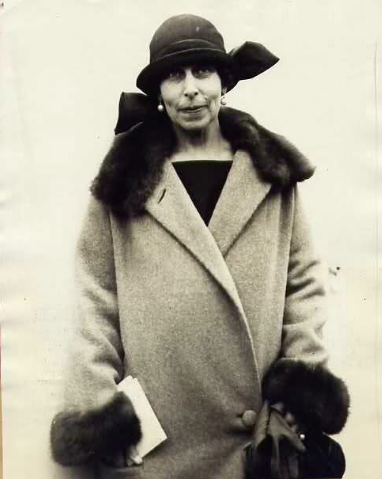

Grand Duchess Kirill on her arrival in New York, 1924.

Mrs. Loomis was right, and her advice certainly holds true today. Mrs. Loomis had arranged for a few trusted reporters to meet the Grand Duchess in her suite on the Paris before disembarking, and the Grand Duchess put to rest some rumors that had been launched by the anti-legitimist cabal. The trip, the Grand Duchess gently insisted, “was purely social, and had been decided upon before her husband had declared himself Emperor.”[61] She went on to defuse the major claims of the Cunliffe-Owen article, saying that the Grand Duke had never had any intention of coming to the United States, that he had never applied for a visa and been rejected, and that those assertions by Cunliffe-Owen were pure fabrication.[62]

The Grand Duchess released a statement to the press before disembarking which went as follows:

The Grand Duchess Cyril has learned of reports appearing in the public press which variously intimated that her visit to this country is for political purposes to help restore the Russian monarchy… The Grand Duchess wishes to invoke the courtesy of the newspapers in publishing a complete and unequivocal denial of these statements and reports. They are without foundation in fact.

Her visit is purely social in nature and has no political or financial purpose. It is made at the invitation of American friends whose invitation she accepted in Paris last summer. The cordial invitation which was then extended to her furnished an opportunity which the Grand Duchess has long desired; to visit a country bound to her own land by ties of traditional friendship, and which has so frequently and generously befriended her countrymen.

She is looking forward with the greatest interest and pleasure to her short stay here; but beyond her expectation of meeting American friends and visiting some places of interest, she has formed no plans.[63]

The old waldorf=Astoria Hotel

Leaving the ship by the Third Class gangplank, which allowed her to have direct access to waiting cars and to avoid press she could not control, the Grand Duchess was ushered into one of three waiting automobiles provided by Mrs. Loomis. Even though this was not an “official” visit, the city provided the Grand Duchess with a security detail, “In view of the possibility that some rabid Bolshevists might try to hurl a bomb at an arriving member of the Russian Imperial Family,” said the acting Police Commissioner[64] who ordered 15 patrolmen posted on the French Line pier for security, and a detail of 10 motorcycle policemen to escort her during her stay. A further security detail of three detectives from the bomb squad were assigned to follow her everywhere and to do advance work while Grand Duchess Victoria was in New York, and they accompanied her to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel with Mrs. Loomis.[65]

The “Empress-in-Exile” (as the press began to call her) had arrived in America, and was about to meet a very different 20th century in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC.

Read Part II next week!

NOTES

[1]“The Visit of the Head of the Romanov Dynasty to America” The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia pub. 19 December 2013, acc. June 22, 2014. www.russianorthodoxchurch.ws/synod/eng2013/20131219_enhihvisit.html

[2]Ibid

[3]In 1871, HIH the Grand Duke Alexis Alexandrovich of Russia arrived in the United States as a guest of the US government to offer thanks for Russian support of the Union during the American Civil War. This first (and only) State Visit by a member of the Russian Imperial House began and ended in New York. Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich visited privately in 1899, as did Grand Duke Boris in 1902 After the Revolution, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the younger) not only visited New York, but lived there for several years, as did Prince Gavril Konstantinovich and Princess Vera Konstantinovna of Russia.

[4]"Wife of Claimant to Czardom Here," New York Times, 7 December 1924.

[5]“Grand Duke Cyril’s Day,” New York Times, 4 January 1899.

[6],“Russian Grand Duke Here,” New York Times3 January 1899.

[7]“Grand Duke Cyril’s Day,” New York Times, 4 January 1899.

[8]The First “Russian Chapel” in New York was located at 851 Second Avenue, near 51stStreet, inside the Russian Consulate. It was known as the “Greco-Russian Consular Chapel” and it was this first that was visited by HIH Grand Duke Alexis Alexandrovich in 1871. By 1894, the Russian Chapel had moved to the new “Church of St. Nicholas” in a converted private house at 290 Second Avenue between 18thand 19th Streets (still standing). By 1905, the congregation had begin their move to 15 East 97th(between 5th and Madison), when, through funding provided by Nicholas II, and through the efforts of Bishop Tikhon and Father Alexander (Hotovitzky), the Cathedral of St. Nicholas was opened.

[9]Bishop Nicholas (Ziorov) of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska (1851-1915), was educated at the Moscow Theological Academy, and became Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the United States. Bishop Nicholas authorized the foundation the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas in New York in 1894, moving it from the Consulate uptown.

[10]St. Raphael (Haweeney) Bishop of Brooklyn (1860-1915), was educated in Damascus and at Halki, and in 1904 was consecrated the first American Orthodox Bishop by St. Tikhon. He founded the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in Brooklyn, and helped found St. Tikhon’s Seminary in Pennsylvania. He was glorified by the Orthodox Church of America in 2000.

[11]St. Alexander (Hotovitzky) (1872-1937) was born in Russia, came to the United States in the 1890’s as a missionary and was ordained here. Active among the Uniates in the U.S., St. Alexander was presbyter of the Church of St. Nicholas until he returned to Russia in 1914, where he was assigned to the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow in 1917. Subsequently subjected to arrests and internal exile, Father Alexander was executed in the purge of 1937. He was glorified in 1994.

[12]The »Русская Беседа» or “Russian Club” was located at 45 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, and was a private organization for Russian subjects in New York.

[13]“Down the River, Mother Volga” is a famous Russian folk song with several very popular 19th century choral arrangements.

[14]“Grand Duke Cyril’s Day,” New York Times, 4 January 1899.

[15]Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, 9th Duchess of Marlborough (1877-1964) cf. Balsan,Consuelo, The Glitter and the Gold, New York: Harper, 1952.)

[16]Julia Dent Grant, Princess Cantacuzène, Countess Spéransky (1876-1975), (cf. Grant, Julia Revolutionary Days: Recollections of Romanoffs and Bolsheviki, 1914-1917 New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919.)

[17]For information on Glyn’s friendship with and patronage by Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna and Victoria Feodorovna, (cf. Gelardi, Julia, From Splendor to Revolution: The Romanov Women, 1847—1928 New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011.)

[18]Anna Gould (1875-1961) daughter of American financier Jay Gould, married firstly the Comte de Castellane, and later his cousin, the Marquis de Talleyrand Périgord, Duc de Sagan. Vastly rich, Gould was a central figure in Belle Époque society in Europe and the United States.

[19]Graf, Harald E. In The Service of the Imperial House of Russia, trans. Vladimir Graf (Falls Church, Virginia: HPB Printing 1998), p. 533.

[20]cf . Mironenko, S. and Maylunas, A., (eds.) A Lifelong Passion, (New York: Doubleday, 1997) pps. 390-416

[21]ibid. p. 532

[22]For more on the title of Curator (Bliustitel’) see: Dumin, Stanislav, Romanovy: Imperatorskii dom v izdnanii, Moscow: Zakharov, 1998, p.117. The primary source is published in Nasledovanie Rossiiskogo Imperatorskogo Prestola, p. 65. See also (for differing views) Massie, Robert K. Romanovs: The Final Chapter, p. 262, and Nazarov, Mikhail Kto naslednik Rossiiskogo Prestola? 2d ed. Moscow: Russkaia Idea, 1998, p. 34.

[23]Grand Duke Kirill, “Manifesto on the Assumption by the Grand Duke Kirill Wladimirovich, Curator of the Imperial Russian Throne, of the Title of Emperor of All the Russias, 31 August/13 September 1924” Russian Imperial House, acc. June 22, 2014 http://www.imperialhouse.ru/eng/dynastyhistory/dinzak3/1109.html

[24] Russell E. Martin, "A Throne which ‘not for an instant might become vacant’: Law and Succession among the Romanov Descendants," (paper presented at the annual conference of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, Boston, Mass., November 2013), 13-19.

[25]Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaevich (1856-1929) was the grandson of Emperor Nicholas I. He steadfastly refused to acknowledge Grand Duke Kirill as Emperor. He had no children. His brother, Grand Duke Peter Nicholaevich, and his nephew HH Prince Roman of Russia (1896-1978), maintained the Nicholaevichi claim after his death against both Kirill and Kirill’s son Vladimir. Prince Roman married without the permission of the Head of the Imperial House, as well as morganatically, placing his two sons, Nicholas and Dimitri Romanovich out of the line of Imperial succession. Both Nicholas and Dimitri Romanov contested the position of Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna as Head of the Imperial House. Neither Nicholas nor Dimitri had sons, and so the Nicholaevichi claim died in their generation. The senior male morganatic descendants of the Romanov Family have always been the descendants of the line of Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, the Princes Romanovsky-Ilyinsky.

[26]Graf, H. p. 185. Dimitry Pavlovich was approached by the Supreme Monarchistic Council, run by Krupensky, Prince Gorchakov, Markov, Talberg, Prince Shirinsky-Shikhmatov, and Kepken. After the death of GD Nicholas, GD Dimitry was asked to take the throne. “Why are you making me this offer?” he asked, “You should know that my leadership would compel you to submit to his Majesty Kirill Vladimirovich.”

[27]Decree of Emperor Nicholas II Concerning the Recognition of the Wedding of Grand Duke Kirill Wladimirovich and Granting to His Wife and Descendants Those Rights Belonging to Members of the Russian Imperial House: To the Governing Senate: Bowing to the request of Our Beloved Uncle, His Imperial Highness Grand Duke Wladimir Alexandrovich, We most graciously decree that the Consort of His Imperial Highness, Grand Duke Kirill Wladimirovich, should be named Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna, with the style Imperial Highness, and that the daughter born of the marriage of Grand Duke Kirill Wladimirovich and Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna, who is named Maria in Holy Baptism, is to be recognized as a Princess of the Blood Imperial, with the style of Highness, which belongs to the Great-Grandchildren of an Emperor. The Governing Senate shall not delay in taking the necessary steps to make this decree public. (The original has been signed in His Imperial Majesty’s own hand:) Nicholas.”

[28]Grand Duchess Victoria’s popularity is examined in depth in the 1913 Book “Behind the Veil of the Russian Court,” By ‘Count Paul Vasili.’ Vasili was the nom de plume of Princess Catherine Radziwiłl (Born St. Petersburg 1858, died New York, 1941). Married to Prince Wilhelm Radziwiłl, Catherine enjoyed unprecedented access to the highest aristocratic gossip of Berlin, Vienna, Prague and St. Petersburg. She wrote under many pseudonyms until, in the 1890’s, her husband discovered her secret literary life, and removed their children from her care, citing her as “unsuitable”. Her life went downhill; she was arrested in Capetown in 1902 for forging Cecil Rhodes’ name on a check, and was divorced by 1906. She was stripped of her prestige and access to information, and the quality of her reportage failed. Subsequent books and articles are filled with obvious fictions rather than simply well sourced gossip, and by 1918 she had become a rumor-mongering society reporter in the US. In 1920, she reported breathlessly that Grand Duchess Kirill had ripped the pearls from the neck of the not-yet-lifeless Grand Duchess Vladimir. (The Washington Post,“News from Foreign Capitals”, 31 October 1920.)

[29]“Aunt Ducky” visited the Grand Duchesses at Tsarskoye Selo, and went with them to inspect the HMS “Lion” and “New Zealand” at Kronstadt on the 14th July, 1914. See Grand Duchess Olga Nicholaevna, The Diary of Olga Romanov, trans. Helen Azar (Yardley, PA.: Westholme Publishing, 2013), p. 6.

[30]While much has been made of the fact that Empress Alexandra Feodorovna “hated” her cousin “Ducky” for divorcing her brother to marry her cousin-in-law, once Nicholas II had reinstated Kirill and Victoria Melita, there appears to have been no official friction. According to the recently translated diaries of Nicholas II’s daughters Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana Nikolaevna, “Uncle Kirill & Aunt Ducky” were certainly regular visitors at the Alexander Palace, and participated in Official engagements together with the Emperor’s daughters—it is hard to sustain any argument of total animosity.

[31]Grand Duchess Victoria, “Letter to Alma Spreckles”,11 February 1922, De Young Museum Legion of Honor, acc. 22 June 2014 http://legionofhonor.famsf.org/blog/framework-imperial-tea-service-peter-carl-faberg

[32]Julia Josephine Stimson Loomis, (1861-1933), was the widow of Dr. Henry Patterson Loomis, noted physician and professor of therapeutics and clinical medicine at Cornell University, and president of the American Academy of Medicine. Julia Loomis was a philanthropist and a leader in the wartime and the postwar relief efforts of French and Russians. She was later decorated for her services in Belgium, France and Yugoslavia. In the late 1920’s, she donated her house in France to become a nursing home for elderly White Russian émigrés.

[33]New York’s first private club for women, which became and remains one of the city’s most distinguished private clubs.

[34]Founded in 1890, The Colonial Dames of America (CDA) is an international society of women members whose direct ancestors held positions of leadership in the thirteen Colonies. The organization's goals are education on US history and historic preservation. Membership is by invitation only, and is limited to female direct descendants of Colonial Governors, Patriots, Commissioned Officers, and few other approved categories.

[35]The “Monday Opera Supper Club” (Now known simply as the “Opera Club”) was founded by private box-holders in the “Diamond Horseshoe” (the first ring of boxes) of the Metropolitan Opera. The Club, with membership by invitation only, was exclusive. The club’s activities expanded from “first night” celebrations, to include small suppers after the performances, annual dances, and by the 1920’s a whole annual program of fundraisers for worthy causes, lecture series on music and politics, and special events. The club is still known in New York as the “Penguin Circle” as members continue to attend each season’s opening night in White Tie.

[36]The Russian Relief Fund was an organization formed during the First World War to provide relief to Russian civilian victims of the First World War. The organization provided funds even before American involvement in the war, and after the revolution, the relief efforts switched to Russian victims of the revolution abroad. The group was officially disbanded shortly before Grand Duchess Victoria’s visit.

[37]Louis Sherry opened his eponymous New York City restaurant at 38th Street and Sixth Avenue. Sherry soon established himself with the clientele known as "The Four Hundred." In 1919, prohibition forced Sherry to close his original restaurant, and he moved to a larger location at 37th Street and Fifth Avenue. Its popularity grew throughout the 1920’s, and again the business moved to 44th Street and Fifth Avenue. Sherry’s closed in 1925, and Louis Sherry died in 1926. The New York Times, “Louis Sherry Dies” 10 June 1926.

[38]It is of interest to note that Grand Duchess Xenia appears with Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Kirill on this invitation, and in correct pre-revolutionary precedence. Grand Duchess Xenia originally recognized Grand Duke Kirill’s right and claim to the throne (cf. Graf, p. 184-185) while her sister Grand Duchess Olga adamantly refused. A generation later, none of the “Alexandrovichi” would support Kirill or his son, and would, in fact, deny that they ever had.

[39]“Social Notes”, The New York Times,16 November 1923

[40]“Ballet For Russian Relief”, The New York Times,20 July 1924

[41]Graf appears to have conflated the Russian Relief Fund with the Society of Colonial Dames or the First Families of Virginia here.

[42]Graf is mistaken here. C. Djamgarov was not Mrs. Loomis’ secretary. Mr. Georges Djamgaroff, a prominent Russian in New York Society, served as Secretary for the Monday Opera Supper Club (See “Grand Duchess Cyril Visit”, New York Times,28 October 1924.)

[43]Graf, p. 91

[44]Graf, p. 92

[45]ibid., p. 94

[46]“Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia Coming”, The New York Times,25 October 1924

[47]ibid.

[48]Frederick Cunliffe-Owen, C.B.E. (1854-1928) was born in London, the elder son of Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen, KCB, KCMG. His mother was born Baroness von Reitzenstein. Educated at Lancing School and the University of Lausanne, Cunliffe-Owen entered the British Diplomatic Service. He served in different parts of the world, until he left the Service and "began to devote his attention to literary pursuits. He came to the United States, where he ‘soon became known as the author of informative and authoritative articles on European affairs and personages.’” (See “Frederick Cunliffe-Owen dies in NYC”, New York Times,30 June 1928)

[49]Cunliffe-Owen, C.F. “The Passing of the Morganatic Marriage: The Abandonment of an Old Royal Custom, No Longer Tolerated by Public Opinion”, New York: 1912.

[50]“Not All Plain Sailing For Cyril”, The New York Times, 2 November 1924.

[51]“City To Entertain Italians”, The New York Times,6 June 1917

[52]In 1917, Ernesto Fabbri was an investor in “Il Carroccio, The Italian Review. Rivista di Coltura, propaganda e difesa italiana in America” published “under the Patronage of H.M. The Queen of Italy.”

[53]H.M. Queen Elena of Italy was born HRH Princess Elena of Montenegro. She was the sister of the Grand Duchess Anastasia, wife of Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaevich, and also the sister of Grand Duchess Militza, wife of Nicholas’ brother, Grand Duke Peter Nicholaevich. This connection is important regarding the appearance of HSH Prince Romanovsky-Leuchtenberg later in this article.

[54] Eleanor Foster Lansing (1866-1934) was the wife of Robert Lansing (1864-1928), Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson from 1915-1920. Mrs. Lansing was herself the daughter of Secretary of State John W. Foster. Eleanor’s older sister Edith was the mother of John Foster Dulles, who also became Secretary of State.

[55]“Prepare for Grand Duchess Cyril”, The New York Times, 5 November 1924.

[56]The Countess was the German-born Baroness Thekla Staal von Greiffenklau, the former wife of Count Alexeï Anatolievitch Orlov-Davydov (1871-1918)

[57]“Grand Duchess Sails”, The New York Times,30 November 1924.

[58]Graf, p. 93

[59]“Grand Duchess Cyril Fêted Near Port”, The New York Times,5 December 1924.

[60]Graf, p. 94

[61]“Wife of Claimant to Czardom Here”, The New York Times,7 December 1924.

[62]ibid

[63]ibid

[64]Richard Edward Enright (1871-1953) NYC Police Commissioner from 1918-1925.

[65] “Wife of Claimant to Czardom Here”, The New York Times, 7 December 1924